Newsletter

Yes! Send me my FREE short story collection and sign me up for those exclusive subscriber goodies!

We value your privacy, and will never spam you! View our privacy policy at lasmithwriter.com/privacy

Yes! Send me my FREE short story collection and sign me up for those exclusive subscriber goodies!

We value your privacy, and will never spam you! View our privacy policy at lasmithwriter.com/privacy

This post is part of an ongoing series of posts on literature from Anglo-Saxon England.

Lnks to other posts in this series can be found at the end of this post.

One of the important sources of surviving literature from Anglo -Saxon England is the Exeter Book. There are only four surviving collections of Anglo-Saxon literature, and of these, the Exeter Book is the oldest, most varied, and the best preserved. I have mentioned this book before in posts on various manuscripts that are found within the book, and I will be highlighting more in the future, but I thought you might find it interesting to know more about the book as a whole.

The Exeter Book was donated to the library of Exeter Cathedral in 1072 AD by Leofric, the first Bishop of Exeter, and there it has stayed ever since. In his will, which details the sixty-seven books and other objects he wished to be donated to the then-impoverished Cathedral, Leofric describes “a large English book of poetic works about all sorts of things,” which is believed to be what is now known as the Exeter Book, or as the Codex Exoniensis. Scholars estimate that is was compiled somewhere between 960-990 AD, and is a collection of various works of religious and secular Anglo-Saxon poetry, including The Wanderer. In fact it contains over 1/6th of the surviving Anglo-Saxon poetry. It also includes over ninety Anglo-Saxon riddles. Several of the poems included in the book are much older than the tenth century compilation date; some go as far back as the seventh century. In many cases the Exeter book contains the only known source of these works. All in all it’s the largest known collection of Anglo-Saxon literature in the world, and as such was recognized by UNESCO in 2016 as one of the “world’s principal cultural artifacts.”

One of the most fascinating entries in the book is The Rhyming Poem, which dates to the tenth century. It consists of Old English rhyming couplets, which is quite different from any other Anglo-Saxon poetry, which was done in alliterative verse.

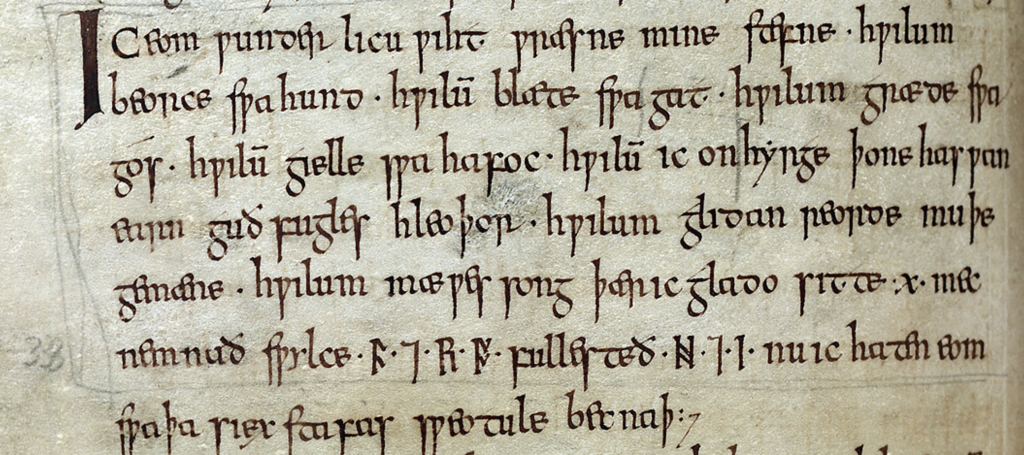

This is an excerpt from Riddle 24 of the Exeter Book. Can you see the runes embedded in this it? They are towards the bottom. This is an example of a riddle-within-a-riddle. In this case the answer to this riddle, which is “magpie” is spelled out by those runes. (see my post on Cynewulf the poet for another example of this). There are other riddles in the Exeter Book which also include runes as an aid for the reader who is able to read both Old English and the runes. Riddle 24 is fairly straightforward, but there are others, even with the aid of the runes, are still so obscure that the riddle has still yet to be solved. Cool, hey? If you want to read more about this, check out this fascinating article from the University of Notre Dame , which is where this image comes from.

The book itself is visually unremarkable, however, especially compared with the beautifully illustrated manuscripts such as the Lindisfarne Gospels or the Book of Kells. It was inscribed with brown ink on vellum, likely copied from an earlier version, and has minimal decorations on a few leaves. A couple of initial letters are slightly ornamented. It has lost its original cover as well as the first original eight pages, which were replaced by others at a later date.

One of the ornamented letters. Image from exeter-cathedral.org

It’s been used as a coaster at some point, you can see the water ring left behind. The early pages are scored through with a sharp object, so perhaps it was also used as a cutting board. The final pages bear some scorch marks. So despite the value of its contents, perhaps its ho-hum appearance was the reason that it was left behind at Exeter Cathedral when a bunch of the Cathedral’s most precious books were donated to the newly founded Bodleian Library at Oxford in 1602 AD. It was obviously not deemed very valuable.

So, it is still at Exeter Cathedral. If you go to visit, you can see it on display there, along with a bunch of other intriguing books and manuscripts, including a Shakespeare Second Folio. But of all of them, the Exeter Book is the greatest treasure.

The Exeter Book still is not recognized today as the important work of literature it is. Most people have barely heard of it, compared with the Diary of Anne Frank or the Magna Carta, both of which have also been recognized by UNESCO and entered into their Memory of the World register.

But that might change. Exeter University professor Emma Cayley began developing an app in 2016 to make the book more accessible to the public. I checked, but it’s not available yet. I hope it is soon! I can’t help but think that Leofric would be pleased.

Links to other posts in this series:

Bald’s Leechbook: The Doctor is In

If you like what you see in my posts, and if you want to be kept up to date with the publication journey of my first novel, Wilding, a historic fantasy set in 7th century England, you should subscribe to my newsletter! You will recieve one approximately once a month, but probably a little more frequently as my hoped-for publication date of October 31st, 2018, approaches. Click here to subscribe. Thank you for your interest in my words!

Featured image: The Exeter Book on display at Exeter Cathedral. The book is open to The Wanderer. Image from UNR English 440A, photo credit UMD iSchool