Newsletter

Yes! Send me my FREE short story collection and sign me up for those exclusive subscriber goodies!

We value your privacy, and will never spam you! View our privacy policy at lasmithwriter.com/privacy

Yes! Send me my FREE short story collection and sign me up for those exclusive subscriber goodies!

We value your privacy, and will never spam you! View our privacy policy at lasmithwriter.com/privacy

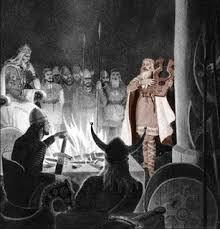

Last week on the blog I wrote about the scops, and their place in 7th century Britain. This week I wanted to touch on the gleemen, and to highlight one particular form of poetry they would use in their entertainment. Riddles, anyone?

To recap, last week I explained that the scop was the poet/singer that wrote poetry extolling the virtues and accomplishments of the king (mostly). He would generally be attached to one court, and not travel around too much.

The other entertainers, called gleemen, were closer to what we think of as the travelling minstrel, who would go from place to place and sing songs and recite poetry in exchange for gifts and presumably, shelter and food. These would generally not compose their own material, but would rely on the work of the scop for their poems and songs. Which was handy for the scop, as it provided a way for the renown of his king to be known far and wide. And his own renown as well, if the songs were popular.

I’m using the word “song” loosely. It’s hard to say exactly how these poems were performed. As I mentioned last week, they might have been recited with the strumming of the lyre used as emphasis in the background. Or, they could have been set to music. There is no musical notations surviving from this era so we really don’t know what it would have sounded like, sadly.

There were other instruments other than the lyre that both scops and gleemen could use, such as drums, horns, and whistles made out of bone or antlers. Other stringed instruments such as the harp, lute, and the early type of violin known as the rebec appeared later, in the 9th to 12th centuries.

This is an illustration from The Vespasian Psalter (prayer book, consisting of the book of Psalms), produced sometime in the second half of the 8th century AD. It adorns Psalm 27, and is meant to show King David playing his harp. It gives us a good look at the instruments of the day: the lyre, the bone whistles, and the horn. Image from wikiwand

It’s possible the scop would begin his career as a gleeman, travelling around and learning his trade, hoping to get good enough to attract the eye of a king or an up-and-coming war leader (who might possibly become king one day) and be invited to become his personal entertainer. He might also have a couple of other musicians travelling with him, but likely it would be just him. It would be easier for ordinary people to provide hospitality (i.e. food and drink) to just one person, rather than a group.

Gleemen, being travellers, would also spread news of what was going on in the kingdom. Most people did not travel much. It was too dangerous and difficult, and going any length of distance meant you had to somehow find food along the way, which was not easy. So having a travelling gleeman stop by your holding would have been a welcome diversion from the hardships of everyday life, both in terms of the entertainment he provided and the news he carried.

Part of that news, of course, would be the battles that the kings had taken part in. This is where the scop’s poems would come in handy. It’s much easier to remember poems than prose, which is why the battles were recounted that way. But there was another popular form of poem which were a type of riddle.

Here is an example, from the Exeter Book, a tenth century collection of Anglo-Saxon poetry, containing poems that dated from much earlier.

| I saw a thing in the dwellings of men that feeds the cattle; has many teeth. The beak is useful to it; it goes downwards, ravages faithfully; pulls homewards; hunts along walls; reaches for roots. Always it finds them, those which are not fast; lets them, the beautiful, when they are fast, stand in quiet in their proper places, brightly shining, growing, blooming. |

Can you guess what the “thing” is? I’ll let you think about it for awhile.*

Here’s another one:

| I am atheling’s shoulder-companion, a warrior’s comrade, dear to my master, a fellow of kings. His fair-haired lady sometimes will lay her hand upon me, a prince’s daughter, noble though she be. I have on my breast what grew in the grove. Sometimes I ride on a proud steed at the army’s head. Hard is my tongue. Often I bring a reward for his words to the singer after his song. Good is my note, and myself am dark-colored. Say what my name is. |

What do you think?**

Tolkien, himself an Anglo-Saxon scholar, used these types of riddles in the Lord of the Rings when Gollum bargains with Bilbo when Bilbo is seeking a way out of Gollum’s caverns.

Of course, Bilbo’s last riddle, “What do I have in my pocket?” is not one of these types of riddles. Bilbo cheated on that one, as Gollum rightly accuses him of doing. Good thing for Bilbo, though!

There are over ninety such riddles in the Exeter Book, covering all sorts of topics, but much has been made of the eight which are the “off-colour” ones. The Anglo-Saxons apparently had a ribald sense of humour (same could be said of us, I suppose), and it shows in these riddles. Here’s an example.

| I’m a wonderful thing, a joy to women, to neighbors useful. I injure no one who lives in a village save only my slayer. I stand up high and steep over the bed; underneath I’m shaggy. Sometimes ventures a young and handsome peasant’s daughter, a maiden proud, to lay hold on me. She seizes me, red, plunders my head, fixes on me fast, feels straightway what meeting me means when she thus approaches, a curly-haired woman. Wet is that eye. |

Er, yes. The answer, of course, is onion. What were you thinking?? Best appreciated in the company of warriors in the mead hall, drinking down the king’s fine ale, methinks.***

Here’s one spoken out loud in Anglo-Saxon, to give you a sense of how the language sounds, and shows you the use of word-puns in the riddle itself. Those Anglo-Saxons were clearly cheeky devils.

To be a person wandering around the country from holding to holding was not without danger. Outlaws along the roads could be a problem, as well as the inherent dangers of always being a stranger, without the backing of kith or kin if something goes wrong. It would have been a hard life in some ways, but it had it’s advantages. I’m sure that there were some who enjoyed this life on the road– heralded wherever he went, showered with gifts. He would have been seen as an exotic figure, knowledgable and mysterious, who has seen the world “out there” and lived to tell the tale, a friend of kings and commoners alike.

He held in his possession the vast treasures of the word-hoard, shared not only with the people of the times but with us today. They, and the scops, are romantic figures who come down to us from the mists of time in the very poems and songs they performed so long ago.

Wouldn’t you love to see one perform? I would. But I’m glad I don’t have to try to beat one in a riddle game!

*Rake

**Horn (Made from an antlers, and often given to a scop in appreciation for his work)

***It’s not just the mead-hall that rang with song after a feast. This was a regular feature of most gatherings, it seemed, Even in the monasteries the monks would pass around the lyre for each to sing for the other’s entertainment after a feast. We know this from Bede, who recounts the story of Caedemon, a lay brother at Whitby Abbey, who was so ashamed of his lack of ability to put words to music that he left a feast before he was put on the spot. During the night he had a vision from God in which he composed a hymn and in the morning he recounted the vision to the Abbess, Hild. Hild was so impressed she encouraged him to take his vows and to learn history and doctrine, which he subsequently turned into verse. He is the first poet whose name is recorded in English history.