Newsletter

Yes! Send me my FREE short story collection and sign me up for those exclusive subscriber goodies!

We value your privacy, and will never spam you! View our privacy policy at lasmithwriter.com/privacy

Yes! Send me my FREE short story collection and sign me up for those exclusive subscriber goodies!

We value your privacy, and will never spam you! View our privacy policy at lasmithwriter.com/privacy

Well I suppose it was inevitable that I would tackle this subject, no? Don’t know why, but for some reason, I have plague on my mind…

Medieval Europe is often associated with a time of plague. There’s a good reason for that. The Bubonic Plague also called the Black Death, devastated Europe from AD 1347-1450. People generally died within three days of becoming ill. The crowded conditions of cities, lack of hygiene, and ignorance of its cause and treatment meant that the plague took a fearsome toll. In some cities, 90% of the population died. Overall, estimates are that the Bubonic Plague killed off up to one-third of Europe’s population in those three short years.

Yeesh. A fearsome, terrible time for those who lived at that time. It’s hard for us to imagine…although perhaps a little less hard, these days.

But what about England in the seventh century? Did they suffer from the plague, too?

The answer is yes. First, a definition. The plague refers to a specific disease, the Bubonic Plague as described above. It is a bacterial infection transmitted to humans from the bites of infected fleas. It is not transmissible human to human, except in the case of the pneumonic plague, which is when the plague bacteria infects the lungs. When someone with pneumonic plague coughs, they can spread the disease to others, which makes it spread much more rapidly.

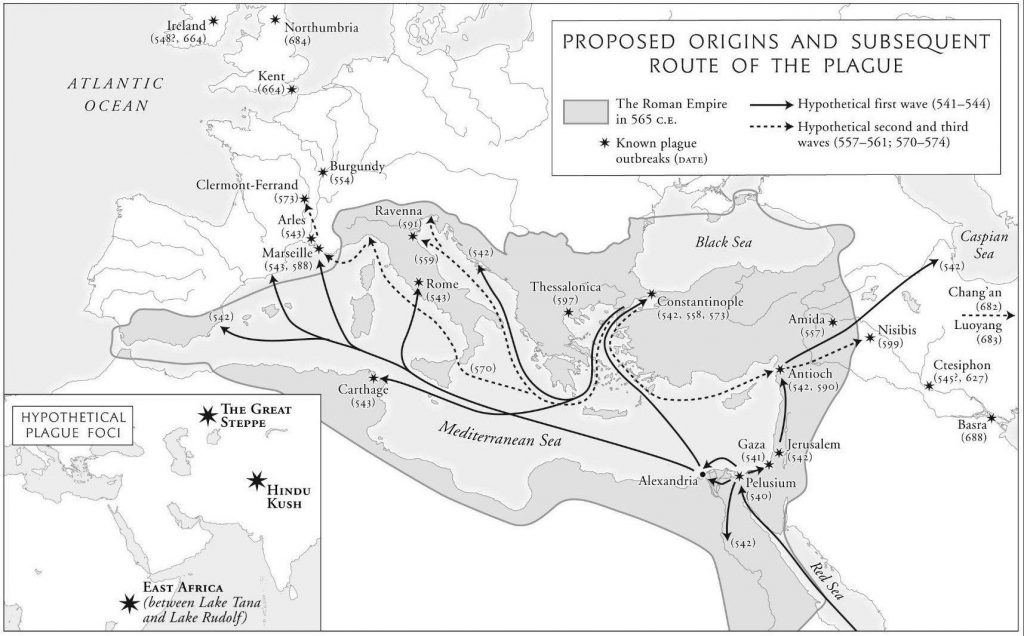

The first documented appearance of the plague was in AD 541 in the Roman Empire, specifically at the Egyptian port of Pelusium. It spread from there across the known world, carried along with the rats on the Roman ships throughout their vast empire. Apparently, the pneumonic form of the plague thrives in cooler weather, and as it happens there was a cold snap in the year AD 540-541 which made it easier for the more easily transmissible form of the plague to spread.* This was not the very first pandemic, but it is the first one that was well-documented enough to be studied with accuracy today.

There are some historians who theorize that this plague was one of the factors that brought about the end of the Roman Empire, because of its depopulating and destabilizing effects. It is called the Plague of Justinian because it began during the reign of Rome’s last significant Emperor.

This plague circulated around Continental Europe, particularly ravaging Byzantium. Some scholars estimate that up to 5000 people per day died in Constantinople at the peak of the epidemic, but it’s hard to know for sure. We do know that the plague circulated around Europe in waves for about two hundred (!) years, until AD 750. Subsequent waves were not as virulent as the first, but all in all the plague took a great toll on the population at the time. There are estimates that 25-100 million people died of the plague over the two centuries. Wow. And then, for whatever reason, it went quiet until the Black Death of the 14th-15th century.

The first appearance of the plague in England was in AD 664, and it circulated around the island for about twenty-five years, ravaging the population. It started in the south and made its way north over that year. There are reports that up to a third of the population of Ireland died from it, but again, it’s hard to know the accuracy of those reports.

Of significant note is that in AD 664, the first year of the epidemic, the plague struck the monastery at Gilling, near present-day York. Eanflaed, the wife of Oswy, King of Northumbria, founded this monastery in AD 652. In AD 664 the plague decimated the brethren at the monastery. It’s not entirely clear from the scanty historical records, but it could be possible that this spelled the end of that monastery. One monk who survived the plague there, Ceolfrith, became abbot of Wearmouth-Jarrow and in AD 685 survived the plague once again when it struck that abbey shortly after its founding, once again with devastating effect. Bede reports that only the Abbot Ceolfrith and one young boy survived to sing the offices and perform the spiritual duties of the monks there. Bede doesn’t say, but it’s clear from inferences in Bede’s writing that the young boy who assisted Ceolfrith was Bede himself. Ceolfrith had likely gained immunity from the first go-round at Gilling, but Bede must have just been lucky (or, as I’m sure he would say, graced by God) not to have caught it himself.

The plague also made its mark by helping to put the nail in the coffin of the Irish Church. I spoke briefly of the Synod of Whitby in my posts about Wilfrid. You might remember from those posts that the Synod happened in AD 664, the very year the plague appeared and started to burn its way through England. Once the Synod was over, and Oswy had ruled in favour of the Roman practices, the Irish Abbots and monks were faced with a decision: to capitulate or to fight back. Some capitulated, some “fought back” by leaving their monasteries and returning to Ireland where the Celtic practices continued for some years before Iona itself changed to the Roman rites in AD 716. But the plague took a great toll on many of the established Irish churchmen who might have had some success in rallying the troops, so to speak, to their side. Because the plague had effectively silenced this opposition and the practitioners of the Roman rites replaced those who died in the monasteries which previously followed the Celtic rites, the transition went much more quickly and smoothly than it might have done.

The plague had its effects on the laypeople, too, of course. Many people died in England, just as they did throughout Europe. Many saw it as a punishment from God. Interestingly enough, Bede himself does not say this, which differs from many of the church leaders who wrote about the Justinian Plague. He saw it as God’s will, but a test of the faithful, not punishment. Partially, of course, this could stem from the fact that the result of the plague in the Church in England was to help reinforce the transition to the Roman rites, of which he heartily approved. But maybe he just had a more spiritually mature outlook on it than his contemporaries did .

While researching this post, I came across a book titled A History of Epidemics in Britain.** It was written in 1891, three years before the bacteria causing the plague was discovered in 1894. See the sidebar for what the author (a doctor, I think?) has to say about the cause of the plague.

The nature of these plagues, beginning with the great invasion of 664, can only be guessed. They have the look of having been due to some poison in the soil, running hither and thither, as the Black Death did seven centuries after, and remaining in the country to break out afresh, not universally as at first, but here and there, as in monasteries….. One naturally thinks of a soil-poison fermenting within and around the monastery walls, and striking down the inmates by a common influence as if at one blow. – Charles Creighton, M.A., M.D.

It’s hard to imagine that the best minds of the 19th century could come up with “soil-poison” as a cause of the plague. How fortunate we are these days to have a much better understanding of these things! The people who lived in the seventh century did have some understanding that the sickness was infectious, but by what means they did not know, other than to think that it was carried in the air (true, in the case of the pneumonic plague!). They did also connect the bodies of the dead as being carriers of disease and so insisted, for sanitary as well as religious purposes, in making sure the dead were buried.

We are facing our very own pandemic today (aren’t we lucky!). It remains to be seen what effect COVID-19 will have on our society and world. Future generations will see that more clearly, I suppose. Because of our better understanding of infectious diseases and our knowledge of this virus, we should be able to avoid the terrible toll in human life that occurred in medieval Europe from the Black Death. Thank God!

But there is no doubt that this modern-day pestilence has already had some profound effects, even if they prove to be temporary. The average person in seventh-century England was much more acquainted with death than we are now. This pandemic has forced many of us to contemplate our mortality in ways that perhaps we have not done before.

There is an old Christian practice called momento mori, “Consider your death”. It was the practice of contemplating the fact that one day you will die. And in light of that, how should you live now?

Depressing? Perhaps. But maybe there is some wisdom there, too.

I hope all of you are staying home, staying safe, and relying on your loved ones to get through these challenging times. Please take care of yourself, physically and mentally!

*Fascinating side note – experts have theorized that a series of volcanic eruptions (or perhaps a comet strike) in AD 536 and again between AD 541-544 caused clouds of ash that decreased the sunlight. That caused crop failures and famine, leading people to be more susceptible to the plague that appeared in AD 541. See this article for more info.

** Here’s the link if you want to have a look…interesting reading, albeit depressing!