Newsletter

Yes! Send me my FREE short story collection and sign me up for those exclusive subscriber goodies!

We value your privacy, and will never spam you! View our privacy policy at lasmithwriter.com/privacy

Yes! Send me my FREE short story collection and sign me up for those exclusive subscriber goodies!

We value your privacy, and will never spam you! View our privacy policy at lasmithwriter.com/privacy

Over the summer I was alerted to two important discoveries from the Anglo-Saxon era in England, and I thought you might be interested in hearing about them, too. It’s so exciting that we are still discovering important artifacts from this long-ago time. Every discovery that is made adds tremendously to our knowledge. It’s tantalizing to wonder what is still out there, awaiting our discovery…

The Prittlewell Royal Burial Site, dubbed “a British version of Tutankhamen’s tomb” by researcher Sophie Jackson in the Independent (May 9, 2019), is not exactly a “new” discovery. In fact, it was discovered way back in 2003, when archeologists did some investigations of a site in Essex, in the south of England, that was due to be part of a road improvement. Anglo-Saxon era graves (as well as other indications of Roman and even older human habitation) had been found in the area in the 1880s, 1920s, and 1930s, so they knew that some archeological investigation needed to be done before doing the road work. But they certainly did not expect to find what they did: an intact burial chamber which included objects of such quality and amount (over 110 objects!) that they knew it had to be a high-status, likely royal, personage who was buried there. In fact, it is only the second intact (i.e. undisturbed) royal burial chamber ever found in England, the first being Sutton Hoo. An amazing discovery, indeed.

This was the mound, before excavation. It’s right in-between a busy road (the one they were going to widen) and a railway line. Somehow it survived intact, for over 1400 years. Image from independent.co.uk

You might wonder why this burial mound, discovered and excavated sixteen years ago, is making news now. It’s because it has taken that long for the archeologists, historians, and scientists to study the grave goods in order to figure out exactly what was in the grave, and to whom the grave belonged. That analysis is now complete enough that in May they were able to reveal what they have discovered so far, much of it new material that hadn’t been reported up to this point.

The chamber was originally a wooden chamber, but the walls and ceiling had gradually collapsed, filling the contents with decayed wood remains and soil. It’s about 13′ square, and is the largest chambered tomb ever found in England.

One of the new pieces of information was the educated guess as to who, exactly, was buried in the tomb. The acidic sandy soil had completely dissolved any remains such as bones, leaving only a few teeth, but even these were so degraded scientists could not find any DNA in them. Originally the dating of the tomb came from dating the gold Merovingian coins found in the tomb. But even that is not as easy as you might think, due to various complicated scientific reasons I won’t go into here. But based on the coins, scientists had thought the individual had been buried there in the early 7th century, and guessed that it could either be Sæberht of Essex, the first Christian king of Essex, or his grandson, Sigeberht II.

But in May, the museum announced that they had been able to do some carbon testing on the tomb, and discovered that it was built earlier that those dates, likely in the late 6th century, from AD 575-605, and they theorize that the occupant could have been Sæberht’s brother, Sæxa, who died before his brother.

Whoever he was, he truly deserved the title “King of Bling”, given to him at the time of the tomb’s discovery. The amount and quality of the grave goods are extraordinary.

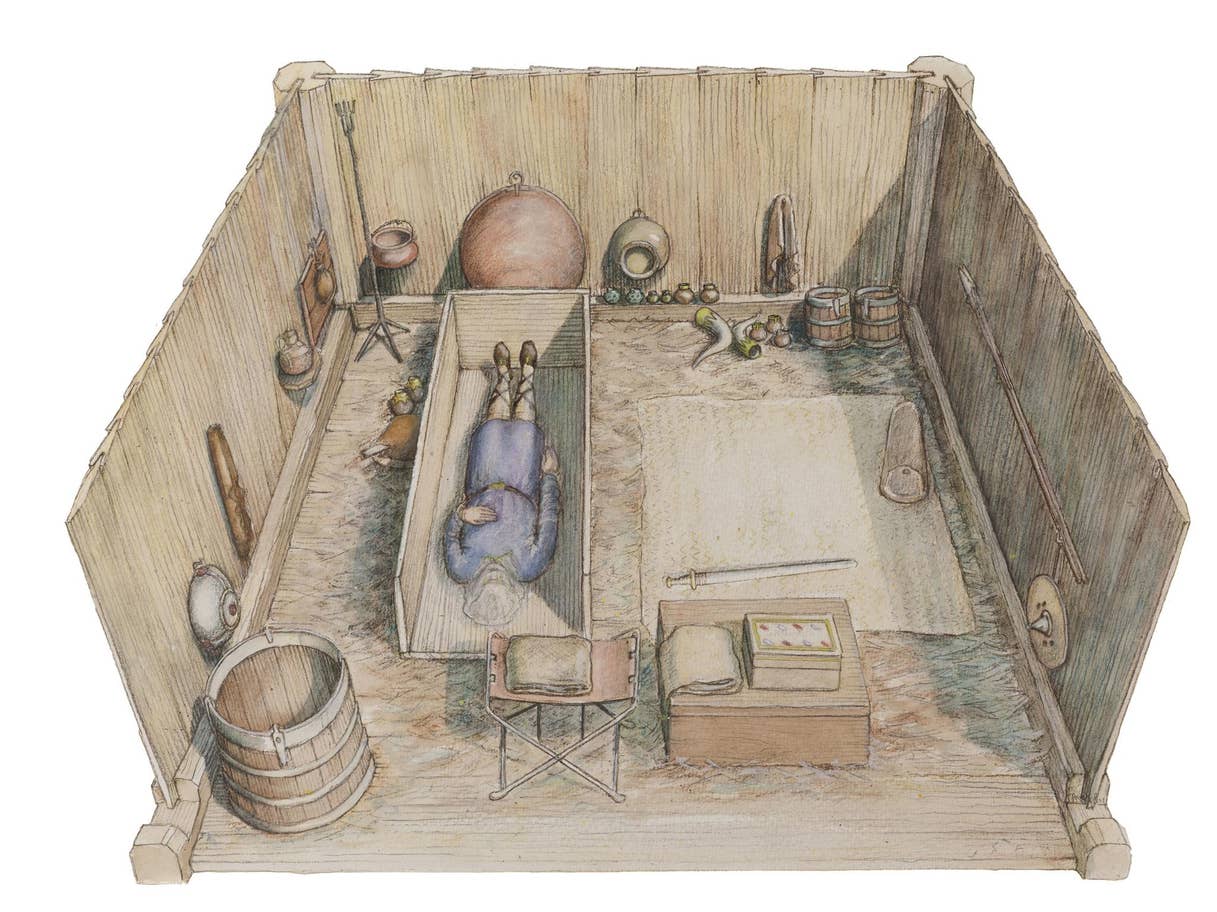

An artist’s rendering of the burial chamber, with the objects in the approximate place in which they were found. The body was in an ash coffin, which is shown open here, but would have been closed. Both body and coffin had been destroyed by the acidic soil, but the iron brackets that held the coffin together remained. Image from independent.co.uk

Here are a few of the objects found in the burial chamber:

A lyre – the instrument itself had completely decayed, but it left behind a stain on the soil, as well as some of the metal fittings. CT scans and other investigations revealed the form of an intact Anglo-Saxon lyre, the first time a complete form of one of these musical instruments from this era has been found. It’s evident that the instrument had been snapped in two at one point and then repaired, showing its value to the owner. Either this man played a lyre or it, along with the drinking horns and flagons, were representative of the feasts at the mead hall he undoubtedly hosted.

A sword – the reason why we know the person buried there is a man is because of the sword (although, to be fair, we have also just recently discovered that a Viking burial long thought to be a man because of the armour and weaponry was actually a woman, so…). This iron blade of the sword has been degraded, but tests reveal it was a typical pattern-welded sword of the time, of the type that would only belong to the very wealthy. Unusually, it was placed outside the coffin, on the floor, in a leather/sheepskin holder and wrapped in cloth. This could demonstrate the clash of cultures/religion at the time. The man was a Christian, as indicated by the gold foil crosses placed over his eyes, but he was buried as a Saxon warrior, with grave goods and weaponry. Placing the sword outside of the coffin could indicate those who buried him were aware of the contradictions involved in this.

Glass goblets – four beautiful blue and green glass goblets.

See what I mean? Beautiful! Image from Flickr

Copper flask – for holding water, this came from Syria, and was often brought back to Europe from Christian pilgrims. Other Mediterranean objects in the grave include a silver spoon and a copper basin. These objects, plus the Sri Lankan garnets on the lyre fittings, show just how cosmopolitan the “Dark Ages” could be.

Folding stool – stools of this type from this era have been found on the Continent, but this is the first one to be found in England. It was possibly a “gift seat” , where the lord would sit while dispensing gifts and/or judgement.

Gold coins – from Merovingian France.

Gold foil crosses – two small crosses, likely placed over the eyes of the deceased.

Painted wooden box – the only painted wood from Anglo-Saxon times found to this date. Only a fragment remains. Inside the box were some objects of special significance to the owner, including a silver spoon, a comb, an iron knife in a holder, fire steel, and some material which might have been undergarments! The featured image above is of the fragment of the box, from independent.co.uk

Shield and other weaponry, including what is thought to be a standard, for carrying heraldry to battle.

And much, much more.

It is truly amazing. If you want a more in-depth look at some of these objects, check out this fascinating link from the Museum of London Archeology.

Or, if you are so lucky to be in England, you can see the objects yourself at the Southend Central Museum.

2. A hoard of Anglo-Saxon/Norma era coins, valued at over $6 million USD.

Yes, you read that right. $6 million USD. Wow. It’s a smaller find in size than the Staffordshire Hoard, but worth more in value, because some of the coins are very rare and therefore very valuable.

The find has been named the Chew Valley Hoard, after an area in North Somerset. These are just some of the coins found. Image by Pippa Pearce, on BBC.com

The hoard of silver coins was found in January 2019 by metal detectorists Adam Staples and Lisa Grace in a field in Somerset (exact location is being kept quiet, for obvious reasons). The find consisted of 2,571 late Anglo-Saxon and early Norman era coins. The really rare coins are the mint condition King Harold II coins. Harold II only reigned for eight months, and died at the Battle of Hastings when the Normans conquered England, so up until this point, few examples of his coins have been found. It is theorized that these coins were likely buried sometime after the battle, probably before 1072.

The detectorists were actually training some friends on how to use their machines that day, and it was one of the friends that found the first coin, one depicting William the Conqueror. The rest of them were found by Grace and Staples.

Not a bad haul for an afternoon’s work, I’d say! Work continues by researchers on analyzing and cataloging the coins. I’m sure we will be hearing more about this stunning find in the months and years to come.

*Fun fact: After the excavation and all the contents of the tomb were taken away by the museum for further study, protestors moved in at the site to prevent the original road-widening plan, as the proposed route would go over the burial site. Protestors camped there for five years (!) until 2009, when an alternate plan was decided. Phew!